Day Five, Tiryns

Tiryns of the Great Walls, the City of Diomedes

Day Five was supposed to have a different schedule, but we woke up to pouring rain, so Sandy and Miranda regrouped and decided to launch Day Six’s itinerary instead. The Nauplion (Nafplio) Archaeological Museum is housed in the old Venetian barracks. It’s beautiful, as are all the Venetian fortifications.

Most of the most spectacular finds from the Argolid are in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens, but we were able to enjoy looking at items from Tiryns in this more intimate setting.

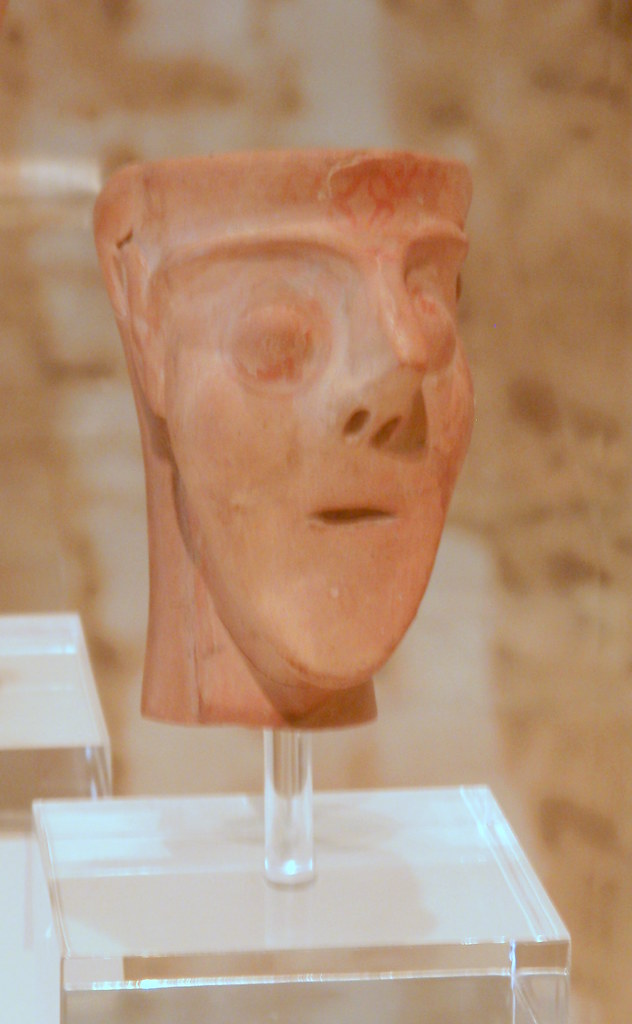

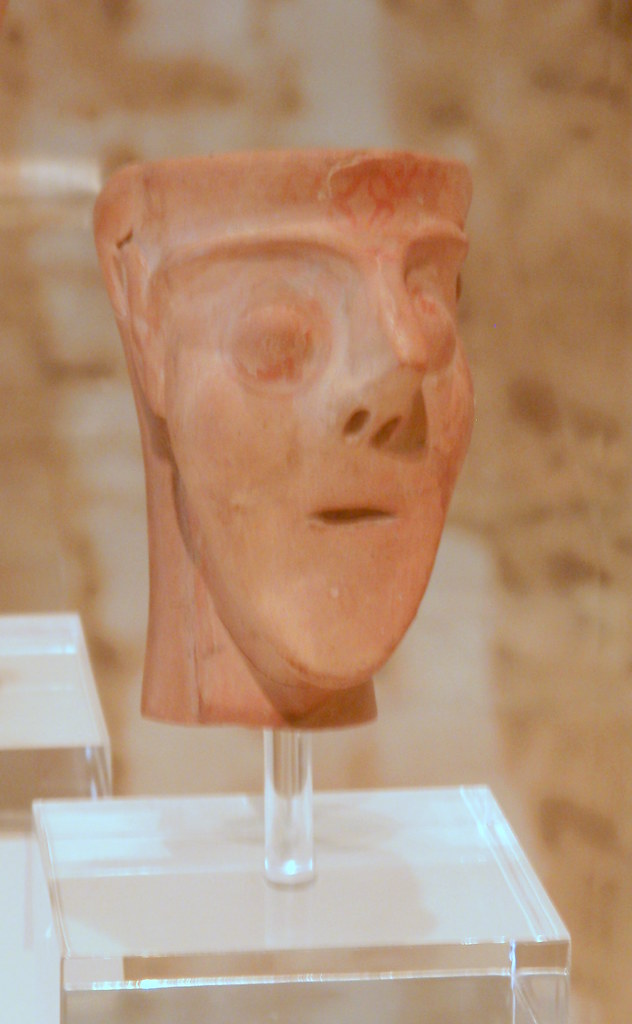

This rather unprepossessing terracotta head, excavated at Asine, inspired the poem, The Lord of Asine, by George Seferis (George Seferiades above).

Seferiades was an exile of the Turkish invasion of Smyrna, his birthplace, who became a diplomat and poet. I think the poem is terrific and would like to read more. Seferis’ famous stanza from Mythistorema was featured in the Opening Ceremony of the 2004 Athens Olympic Games::

I woke with this marble head in my hands;

It exhausts my elbows and I don’t know where to put it down.

It was falling into the dream as I was coming out of the dream.

So our life became one and it will be very difficult for it to separate again

In 1963, Seferis was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature “for his eminent lyrical writing, inspired by a deep feeling for the Hellenic world of culture.” in his acceptance speech, Seferis chose rather to emphasize his own humanist philosophy, concluding: “When on his way to Thebes Oedipus encountered the Sphinx, his answer to its riddle was: ‘Man’. That simple word destroyed the monster. We have many monsters to destroy. Let us think of the answer of Oedipus.”

Here’s the Poem about the Lord of Asine:

The King of Asini

By George Seferis

All morning long we looked around the citadel

starting from the shaded side there where the sea

green and without lustre — breast of a slain peacock —

received us like time without an opening in it.

Veins of rock dropped down from high above,

twisted vines, naked, many-branched, coming alive

at the water’s touch, while the eye following them

struggled to escape the monotonous see-saw motion,

growing weaker and weaker.

On the sunny side a long empty beach

and the light striking diamonds on the huge walls.

No living thing, the wild doves gone

and the king of Asini, whom we’ve been trying to find for two years now,

unknown, forgotten by all, even by Homer,

only one word in the Iliad and that uncertain,

thrown here like the gold burial mask.

You touched it, remember its sound? Hollow in the light

like a dry jar in dug earth:

the same sound that our oars make in the sea.

The king of Asini a void under the mask

everywhere with us everywhere with us, under a name:

‘’??í??? ??. . .’??í??? ??. . .’

and his children statues

and his desires the fluttering of birds, and the wind

in the gaps between his thoughts, and his ships

anchored in a vanished port:

under the mask a void.

Behind the large eyes the curved lips the curls

carved in relief on the gold cover of our existence

a dark spot that you see travelling like a fish

in the dawn calm of the sea:

a void everywhere with us.

And the bird, a wing broken,

that flew away last winter

— tabernacle of life —

and the young woman who left to play

with the dog-teeth of summer

and the soul that sought the lower world gibbering

and the country like a large plane-leaf swept along by the torrent of the sun

with the ancient monuments and the contemporary sorrow.

And the poet lingers, looking at the stones, and asks himself

does there really exist

among these ruined lines, edges, points, hollows and curves

does there really exist

here where one meets the path of rain, wind and ruin

does there exist the movement of the face, shape of the tenderness

of those who’ve waned so strangely in our lives,

those who remained the shadow of waves and thoughts with the sea’s boundlessness

or perhaps no, nothing is left but the weight

the nostalgia for the weight of a living existence

there where we now remain unsubstantial, bending

like the branches of a terrible willow tree heaped in unremitting despair

while the yellow current slowly carries down rushes uprooted in the mud

image of a form that the sentence to everlasting bitterness has turned to stone:

the poet a void.

Shieldbearer, the sun climbed warring,

and from the depths of the cave a startled bat

hit the light as an arrow hits a shield:

‘’??í??? ??. . .’??í??? ??. . .’. If only that could be the king of Asini

we’ve been searching for so carefully on this acropolis

sometimes touching with our fingers his touch upon the stones.

Asini, summer ’38—Athens, Jan. ’40

His poetry so achingly conveys the longing to reimagine and connect with the past.

Bronze Helmet from Tiryns, Shaft Grave XXVIII, 1050-1025 BC

No one knows how these masks (below) were used. Although human head sized, it didn’t appear that anyone could actually put it on their head. One of our group suggested that they might have been used as chimney pots, which actually seemed a sensible idea – they’re the right size and look like gargoyles, but there is no evidence of smoke or burning in the clay. So, alas, they are not chimney pots.

Ceremonial Mask, Tiryns Upper Sanctuary, “Bothros”, 7th Century BC

These ritual masks totally remind me of the toothsome demons of Thai dance. Anyway, they’re curious.

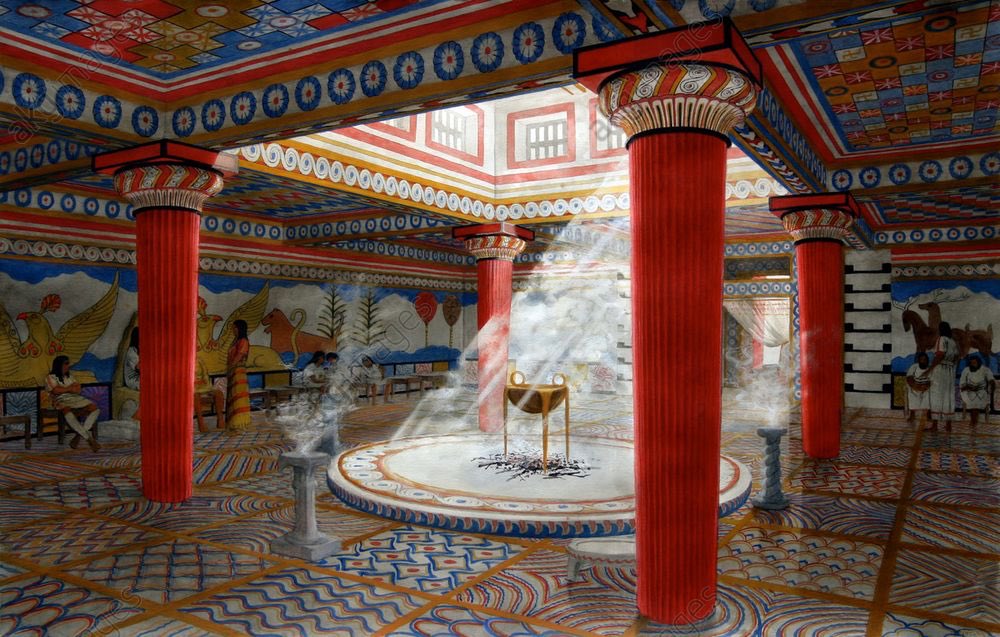

The museum contained items from all over the Argolid, ranging from Neolithic to Classical. Since I’m primarily interested in the Mycenaean, however, I’m only showing those. One of the things I love most about Minoan and Mycenaean palaces are the frescos on the walls, ceilings and floors. I have a concrete room below the front steps of my house, which we use as a storage room and storm shelter. I’ve been feeling the compulsion to paint the inside like a Bronze Age Palace for years. I think it would make a great winter project. I’ve even toyed with the idea of trying to do actual frescos. At the moment, however, the room is subject to damp, which I think would be very bad for an application of plaster. I will seal the walls, of course, and they don’t actually leak, but the room now has a door on it, so unless I leave it wide open, the dehumidifier doesn’t have an effect on the walls in there. I can certainly paint it to look like fresco; that would be the easier course. Someday I’d like to actually try doing a frescoed wall. It’s interesting that the Minoans and Mycenaeans both frescoed their floors as well and the floors stood up to being walked on. I don’t imagine any of the inhabitants were wearing spiked heels, so their footwear wasn’t quite as damaging, but every surface of their rooms were patterned and muraled. Dolphins and seascapes were a favorite theme for floors.

Fresco with rosettes and running spirals with a papyrus flower in the angles, Palace at Tiryns, 13th Century BC

Tripod for Griddle Tray, Tiryns, 1250-1180 BC

The famous Dendra Armor, bronze with a completely intact Boars Tooth Helmet, is at the Museum at Nauplion. I first heard of this find in Denys Page’s History and the Homeric Iliad, which I read for my Freshman Interim paper on Greek Mythology. I initially studied Greek just so I could read the footnotes in this book. Sandy kept saying that Nestor wore a Boars Tusk helmet whenever he referred to it. I whispered in an aside to Geneia that, to the contrary, it was Odysseus who wore the helmet.

Meriones gave Odysseus a bow, a quiver and a sword, and put a cleverly made leather helmet on his head. On the inside there was a strong lining on interwoven straps, onto which a felt cap had been sewn in. The outside was cleverly adorned all around with rows of white tusks from a shiny-toothed boar, the tusks running in alternate directions in each row.

—?Homer, Iliad 10.260–5

Do I know my subject, or what? It wasn’t Nestor.

This suit of armor predates the Trojan War, which is a relief to me. I wouldn’t have liked to think of the heroes boffing each other in such awkward kit. Denys Page, way back in the 60s, said the Boar’s Tusk Helmet was a throw-back to the 16th Century BC. (The account in Homer does say that Odysseus inherited it.)

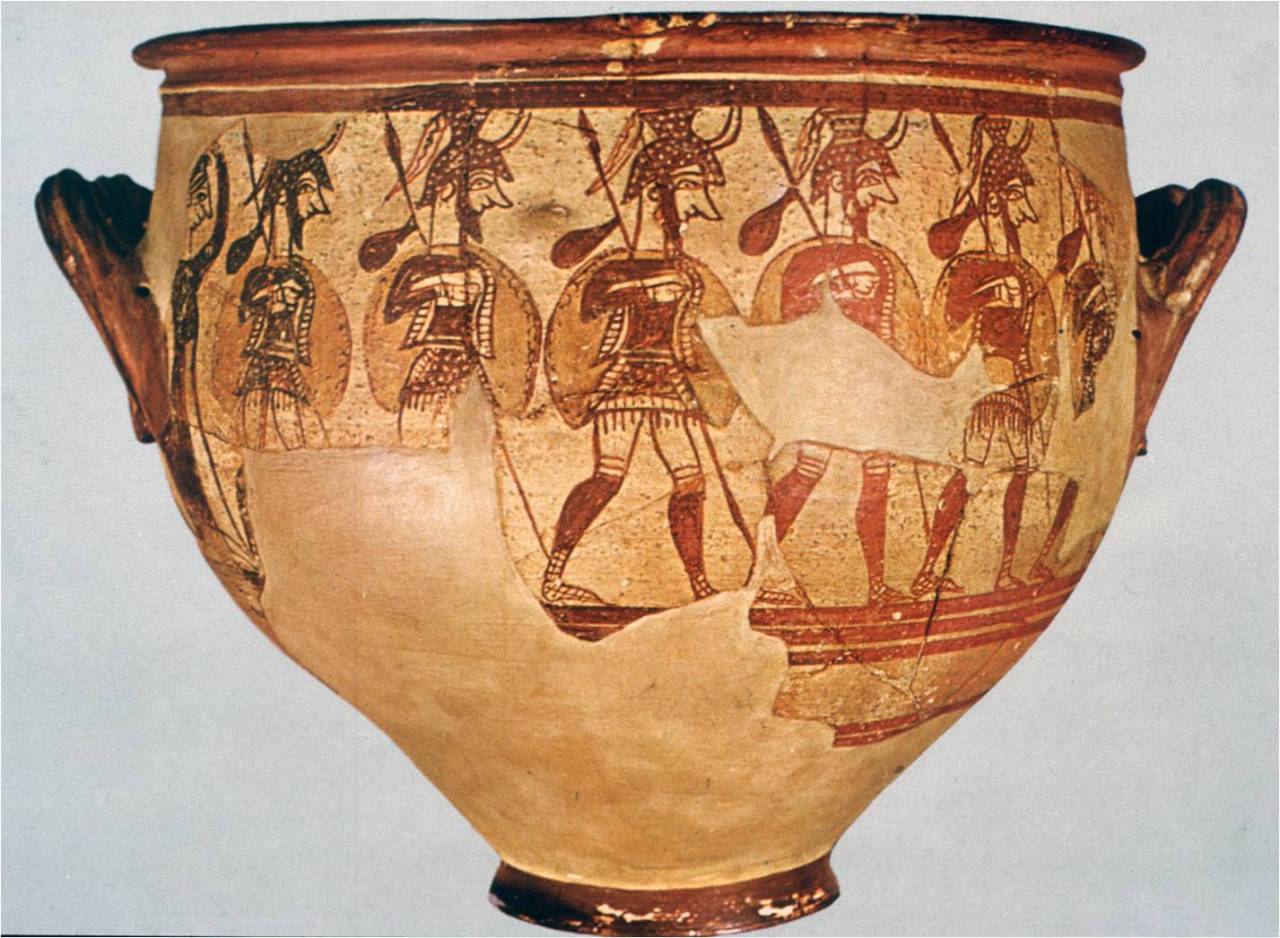

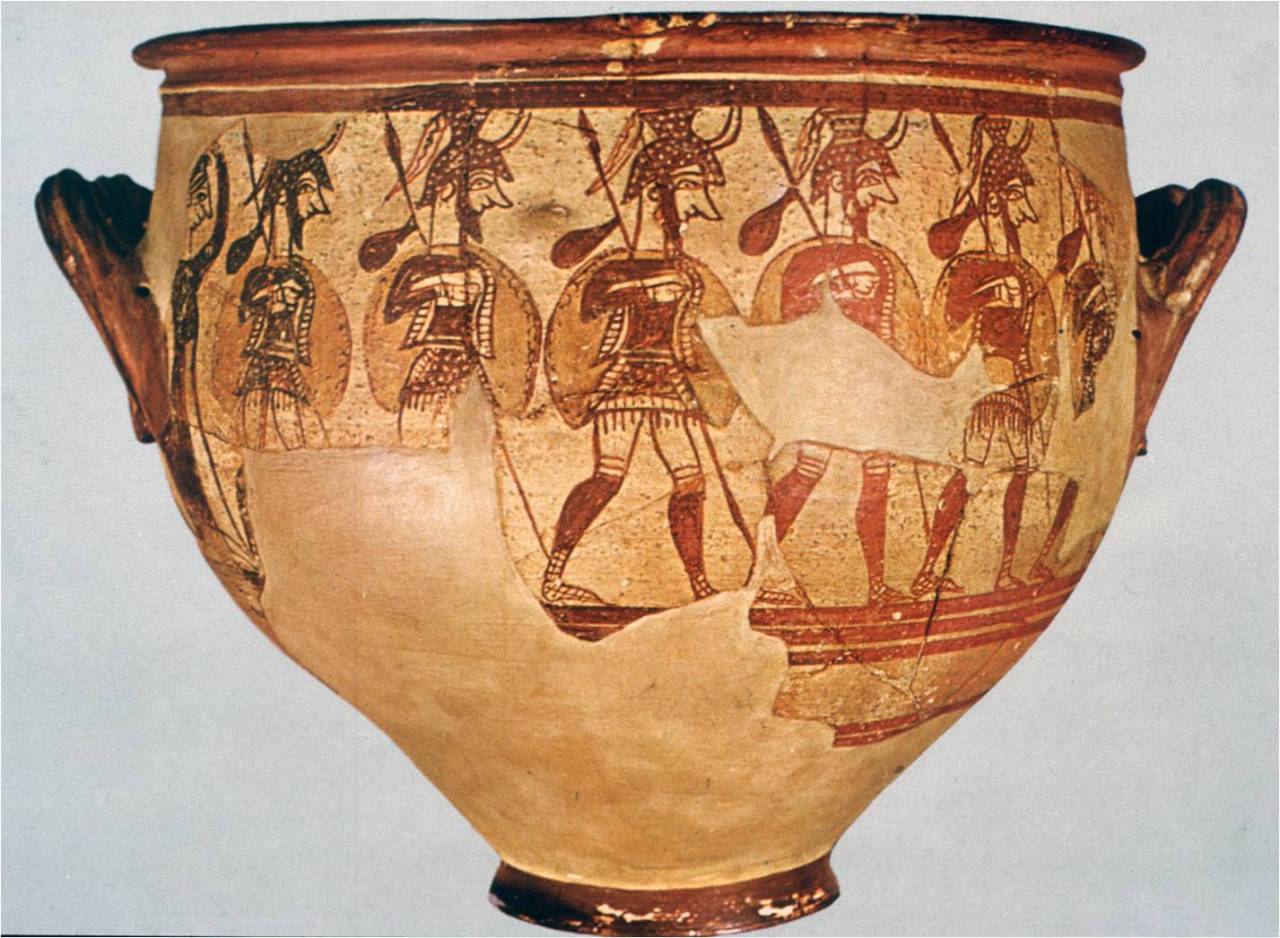

I like the helmet, but the bronze armor….not so much. To substantiate the Trojans and Achaians wearing something different, there are the figures on the Warrior Vase (Mycenae, ca 1200 BC in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens,),

They are wearing a different body armour. It may be either an embossed waist-length leather corslet with a fringed leather apron that reaches to mid-thigh and possible shoulder-guards, very much like that worn by the Peoples of the Sea depicted on the mortuary temple of Rameses III (died c. 1155 BC) at Medinet Habu, Lower Egypt, or, alternatively, the body armour may be a ‘bell’ corselet of beaten bronze sheet, a type also found in central Europe at that time.

From Nauplion, we drove to Tiryns, to view it in the rain. Fortunately I’d brought an umbrella and raincoat with me on the trip and this was the second time I was using them. When we bought our tickets the guide warned us against standing on the height with umbrellas, lest we attract lightning. (Apparently that had happened to someone at Mycenae only a month ago.) However — come on — we’d come half way across the world to see this, so the warning fell upon deaf ears, just as it had at Delphi. Tiryns is very close to Nauplion and close to the road. Like Stonehenge, you pass it constantly, and it’s a wonder that it’s not more famous to non-Homeric-geeks, because the stupendous walls are better preserved than they are at Mycenae. It just doesn’t have that great Coat of Arms, the Lion Gate, anymore. The pediment of the gate is gone. It’s on a hill, but the hill isn’t as high.

Tiryns on a sunny day.

But Tiryns is formidable. I can’t even say the name without mumbling, “great walled Tiryns” under my breath. I mean, they were seventeen feet thick! (Come to think of it; I’m pulling that up out of my memory of Denys Page.)

The megaron of the palace of Tiryns has a large reception hall, the main room of which had a throne placed against the right wall and a central hearth bordered by four Minoan style wooden columns that served as supports for the roof. Two of the three walls of the megaron were incorporated into a temple of Hera in the Archaic Period. In 1300 BC, the citadel and lower town had a population of 10,000 people.

There is much evidence that Bronze Age Greece was matrilineal. Diomedes succeeded his maternal grandfather, Adrastus, to become King of Tiryns and the Argolid. Menelaus became King of Sparta by marrying the heiress, Helen. Even though she had two brothers, Castor and Pollux, there is never any suggestion that one of them might have succeeded to the throne. From Helen and Menelaus, the throne of Sparta then passed on to her daughter, Hermione. Oediupus became King of Thebes by marrying Jocasta. Clytemnestra, though, like Helen, from Sparta, bestowed the throne of Mycenae on her lover, Aegisthus, while Agamemnon – her second husband, by the way — was away at Troy (possibly because he had sacrificed the heiress, Iphigeneia?). While Odysseus is absent from Ithaka for twenty years, Penelope is plagued with would-be new husbands, who would then succeed to the Kingship by marrying her. Interesting, no?

The following is from Women in the Aegean: Minoan Snake Goddess by Christopher L.C.E.

For “matriarchy to have had some validity, and in order for a Classical Greek theatre audience to accept the fact that women such as Helen, Clytemnestra, Antigone, Iphigenia, Hecuba, Andromache, Penelope, Medea, Alcestis, and Elektra (fully half of all extant 5th century plays have powerful women in leading roles) could indeed threaten patriarchal social order or alter the course of history, it must have had some basis in historical reality. The “historical” situation of the majority of the myths and legends is the Bronze Age, during or near the end of the Minoan civilization, and the “reality” may have been not matriarchy per se but rather matriliny.

A common feature of patriarchal and patrilineal cultures is “virilocality” (or patrilocality), which means that when a man and woman marry, the wife goes to live at her husband’s family’s residence. A distinguishing feature of matrilineal cultures is “uxorilocality” (or matrilocality), which means that the husband goes to live at his wife’s family’s residence.

Evidence of uxorilocality can be found in various myths and legends which are “historically” situated in the Bronze Age. For example, in the well-known story of Helen, when Menelaos first marries her, he travels to live with her in Sparta where he rules as king, even though Helen has two worthy brothers, Kastor and Polydeukes (Castor and Pollux). Menelaos attains the kingship of Sparta through his marriage to Helen who carries the bloodline of the Lakedaimonian throne.

When Helen is abducted by Paris and taken off to Troy, Menelaos, his position as king thereby made insecure, makes every effort to get her back, enlisting the help of all Greece. When during the course of the siege of Troy Paris and Menelaos agree to fight in single combat, the prize is not only Helen but “all her possessions.” Later, after Helen’s death, it is her daughter, Hermione, and not one of Menelaos’ sons, who becomes the next ruler of Sparta.

Helen was the daughter of Leda who was ostensibly married to Tyndareus. Tyndareus, however, was not the father of Helen. Later tellers of the story, no doubt uncomfortable with Leda’s evident promiscuousness and lack of adherence to patriarchal laws of male inheritance, interpolated the myth of Leda’s seduction by Zeus as a more satisfactory explanation of her behaviour.

Leda’s case is by no means unique. Bronze Age myths and legends are filled with important children whose mother is named but not their father. These children obviously had a human father, and one who wasn’t necessarily the husband of their mother, but when the stories were retold this affront to patriarchal sensibilities was softened with the explanation that each child was in fact fathered by a god.

Helen’s sister was Clytemnestra who moved away from Sparta to Mycenae when she married Agamemnon. However, in true matrilineal form, she feels no compunction after Agamemnon leaves for Troy of taking Aegisthus as her consort-king with whom she rules Mycenae. And doubtless she felt quite justified in having Agamemnon killed upon his return after he had committed the sin of murdering Clytemnestra’s heiress-daughter Iphigenia.

Another possible instance of matriliny is to be found in the story of Penelope who, following the departure of Odysseus, appears to have been regarded as the heiress-queen of Ithaka whose hand was sought by the suitors hoping thereby to be made king. Crete is referred to several times in the story of Odysseus; he had visited the island in his travels and when he returns home to Ithaka while in disguise he tells everyone the “lie” that he had just come from Crete.

Minoan Crete, however, has also been suggested as the real identity of the island of the Phaiakans upon which Odysseus had been shipwrecked and where he met Nausikaa (Odyssey, Books 6 and 7). Although perhaps no more than a folk-memory by the time Homer was writing, the story describes a matrilineal society wherein, for example, Nausikaa invites Odysseus to marry her and settle in her family’s residence (an uxorilocal arrangement). Moreover, Odysseus is instructed to supplicate not the king, Alcinous, but Queen Arete, implying thereby that it is the queen who will determine Odysseus’ eligibility to marry the heiress-princess Nausikaa and thereby become king.

Other stories not narrated by Homer which illustrate matrilineal succession to the royal throne include the marriages of Atalanta, Hippodamia, and Jocasta. These and other clues embedded in Bronze Age myths and legends indicate patterns of marriage and inheritance which suggest that matriliny was to be found among pre-Greek Aegean cultures.”

On the other hand, there are stories of brothers fighting for a throne, as Polydeuces and Eteocles, Antigone’s brothers, for Thebes, and Proetus and Acrisius for Tiryns, so it must have been a period of flux. There are the Dorians that were coming in.

This Indo-European “invasion” was already underway by the 13th century BCE when a primitive written Greek appears in Linear B, a script based on the earlier, and as yet undeciphered, non-Greek Linear A which was already flourishing on Minoan Crete as early as 1700 BCE. Linguists recognize that a number of ostensibly “Greek” names – such as Odysseus, Achilles, Theseus, Athene, Hera, Aphrodite, Hermes, Knossos, Mycenae, for example – are in fact non-Indo-European and belong to a pre-Greek language (or languages) that was spoken in Greece and perhaps throughout the Eastern Mediterranean, including Minoan Crete. (ibid.)

The fact that women had much more influential positions in society is one of the reasons I’m still interested in the Bronze Age and can barely bear to read about the Classical. I’m about to read a book about Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women Across the Ancient World. The protagonist of my novel, if you remember, masquerades as an Amazon, so I’m glad that there have now been these discoveries in Russia of the graves of warrior women from the Caucasus to substantiate the myths.. Andrea is already reading this, but I’m still in Out of Isak Dinesen in Africa by Linda Donelson.

Asine, our next stop, was another Mycenaean stronghold, one of the holdings of Diomedes, but there was little left of it except machine gun nests created by the Italians during WW II. There was a Cyclopean wall, modified during the Hellenistic Era, and Mycenaean necropolis with many chamber tombs. Excavations have been undertaken since 1922 by Sweden.

This was to be the day when we would have a chance to go swimming — there was a beach directly beneath the fortifications – but because the day had begun with rain, none of us had brought out swimsuits with us. Asine certainly had the best view, with an islanded bay banked by many headlands.

Alas for a swim…..

Since we had some time before dinner, Geneia and I walked along the sea wall outside of Nauplion to look for the swimming beach. We weren’t going to swim anymore, but we hadn’t really had a look about as yet.

The swimming beach is at the end of the Sea Wall

The next day, Friday, we did what we had originally been scheduled to do on Thursday; we went to see the Bronze Age cemetery at Dendra. This is where the bronze armor was found. There were a number of chamber tombs and a tholos tomb, actually most of which were excavated by the Swedes in the first half of the 20th Century. One that had not been looted contained the bronze panoply, but on the very night of the discovery, everything except the armor and helmet were stolen. There were several horse burials too.

From Dendra, we went to see the Hereion of Argos. The Heraion of Argos was part of the greatest sanctuary in the Argolid, dedicated to Hera, whose epithet “Argive Hera” (??? ?????? Here Argeie) appears in Homer’s works. Hera herself claims to be the protector of Argos in Iliad IV, 50–52): “The three towns I love best are Argos, Sparta and Mycenae of the broad streets”. The memory was preserved at Argos of an archaic, aniconic pillar representation of the Great Goddess. The site, might mark the introduction of the cult of Hera in mainland Greece; it lies northeast of Argos between Mycenae and Midea. Pausanias, visiting the site in the 2nd Century CE, referred to his area in between as Prosymna. The Hereion is where Agamemnon is supposed to have been elected as leader for the Trojan War expedition in this place. The source of that tale is someone I’ve never heard of before, Dictys of Crete.

Here is what Wikipedia says of him:

Dictys Cretensis of Knossus was the legendary companion of Idomeneus during the Trojan War, and the purported author of a diary of its events, that deployed some of the same materials worked up by Homer for the Iliad. With the rise in credulity in late antiquity, the story of his journal, an amusing fiction addressed to a knowledgeable and sophisticated Alexandrian audience, came to be taken literally.

In the 4th century AD a certain Q. Septimius brought out Dictys Cretensis Ephemeridos belli Trojani, (“Dictys of Crete, chronicle of the Trojan War”) in six books, a work that professed to be a Latin translation of the Greek version. Its chief interest lies in the fact that, as knowledge of Greek waned and disappeared in Western Europe, this and the De excidio Trojae of Dares Phrygius were the sources from which the Homeric legends were transmitted to the Romance literature of the Middle Ages.

I had no idea.

An elaborate prologue to the Latin text details how the manuscript of this work, written in Phoenician characters on tablets of limewood or tree bark, survived: it was said to have been enclosed in a leaden box and buried with its author, according to his wishes.

“There it remained undisturbed for ages, when in the thirteenth year of Nero’s reign, the sepulchre was burst open by a terrible earthquake, the coffer was exposed to view, and observed by some shepherds, who, having ascertained that it did not, as they had at first hoped, contain a treasure, conveyed it to their master Eupraxis (or Eupraxides), who in his turn presented it to Rutilius Rufus, the Roman governor of the province, by whom both Eupraxis and the casket were despatched to the emperor. Nero, upon learning that the letters were Phoenician, summoned to his presence men skilled in that language, by whom the contents were explained. The whole having been translated into Greek, was deposited in one of the public

Temple of Hera

libraries, and Eupraxis was dismissed loaded with rewards.” (Smith, Dictionary)…Modern scholars were in disagreement as to whether any Greek original really existed; but all doubt on the point was removed by the discovery of a fragment in Greek amongst the Oxrhyncus papyri found by Bernard Grenfell and Arthur Hung in 1899–1900. It revealed that the Latin was a close translation. The other surprise was the discovery, in the library of Conte Aurelio Guglielmo Balleani at Jesi of a manuscript of Dictys, in large part of the ninth century, that was described and collated by C. Annibaldi in 1907.

It’s funny. I never wondered what sources medieval poets used for stories from the Trojan War – I thought Homer was the stimulus for all their compositions..

Remains of the Stoa

There had been a Mycenaean cemetery in this location as well, but the remains are from the Classical Period; I’m afraid I didn’t listen very closely as a result.

There was a festival in the Square in Nauplion that evening before our lecture. Because I spent some time writing up my notes, Geneia and I strolled down there late and missed the dancing. I did get to see them strolling down the street, with the men playing accordions, walking and singing like minstrels.

On our last day, we visited Nemea. In order to check in for our flight 24 hours early, I got up at 6:15, but wasn’t able to do it. I had the same problem I’d had in Mineral Point, but had forgotten the solution. I needed to sign in as Nona B, instead of Nona Hyytinen, so I tried again at lunch, finally figuring it out, but ran out of time before the bus was leaving the restaurant. I was able to sign in when we finally made it back to the Herodion in Athens, however.

We had an especially privileged experience visiting Nemea. The archaeologist from the University of California (American Society for Classical Studies), Stephen Miller, was on hand at the site to talk to us and show us around. Nemea was a shrine dedicated to Zeus, Nemean Zeus (a milder version who didn’t throw thunderbolts). It was one of the locations for Panhellenic Games.

The rather strange foundation myth for the Nemean Games – having nothing to do with Heracles and the Nemean Lion, as I expected – has rather to do with the baby of King Lykourgos and Eurydike, his wife, named Opheltes. He was a long awaited son, but when he was born and the proud father visited Delphi looking for some sort of propitious advice from Apollo concerning their son’s future and upbringing, they were told that he would not live if he ever touched the ground before he could walk. A nurse was promptly assigned to him, carrying him wherever he would go.

This nurse, a slave who was a princess in her homeland, was one day arrested in her perambulations by seven men on their way to attack Thebes, the famous Seven Against Thebes of Sophocles. (These Seven, with the exception of Oedipus’ son Polynices, were all from Argos and were in league with Polynices to wrest the throne of Thebes away from Oedipus’ other son, Eteocles. Now, Eteocles is a character in my novel. The Hittite name, Tawagalawash, which figures in a famous letter from Hattusilis III to the King of Ahhiyawa — Achaia or, in Mycenaean times, Achaiwa — is probably the same name as Eteocles in its Mycenaean form, Etewoklewes. (I haven’t decided yet which form of the name to use. I don’t know if you remember, but my protagonist, Eden, ends up pulling a dagger on him during a banquet, because he’s a little too amorous.)

Anyway, the nurse/princess put the baby down on a patch of wild celery, so he wouldn’t actually touch the ground, but a serpent came out and bit him and…prophesy fulfilled, the baby died. Distressed by his death, the Seven decided it was in inauspicious omen for their own enterprise, so they they held funeral games in his honor and that was the beginning of the Nemean games. Wild celery was the crown of victory, black robes were worn by the judges and a grove of cypresses were planted around the Temple of Zeus.

The first games were held in 573 B.C. I don’t know how that corresponds with the Seven Against Thebes, since that is from a Bronze Age myth, but perhaps it was supposed to be a revival of the original funeral games.

According to Stephen Miller, when he first came to excavate Nemea, he was embraced by the mayor of the area, a man named Parmenion Demitriou, as a “savior.” Demitriou had long wanted to excavate the stadium; he knew where it was and had actually gathered affidavits from all the land owners whose property touched the stadium grounds, stating that they would sell their land for 4 drachmas per acre. Menio said he would give them to Miller if Miller would uncover the stadium – of course Miller was there to do that very thing – but, the second proviso was that he revive the Nemean Games.

Stephen related the story of his first season digging. It turned up absolutely nothing, nada. In despair over receiving any funding to continue next season, he arranged for a one week extension – possibly at his own expense; I can’t quite remember – and on Tuesday of that week, they finally found a coin. Coins are definitely cool, but one coin is a pretty small find. On the Friday, to their great relief, they uncovered the starting stones, so he could go to his sponsors with a reason they should fund the dig for another season.

Menio got to see the excavated Stadium before he died and knew that Stephen was going to fulfill his request to hold the Games once more. He died before seeing it happen just a month or so afterward.

After the first Nemean Race in millennia, Menio’s son, Kostas, came to Miller, saying that now the games had been revived, they must go on. The two of them must make it happen. (By the way, Miller’s team had discovered a fantastic tunnel leading to the track, under an intervening hill, through which the athletes would come from the building where they dressed. Apparently, before it was discovered, no one had thought that the Greeks were capable of building a tunnel before the Romans came along and showed them how. This whole controversy hung upon whether Macedonians were Greek or not. Amazingly – despite the fact that Macedonian conquest led to the Hellenistic Period…hello — there was a time when scholars debated whether Macedonians were indeed Greek. The thing was, Philip of Macedon was the one who had built the tunnel, after he’d overrun Greece, so scholars were debating whether Greeks had the know-how.)

The Nemean Games have been held every four years since. According to Menio’s stipulation, the races are run barefoot in khitons, but the participants can be just anyone, not just athletes. Persons from all over the world have participated. Emily should do this; I mean it! How cool would that be. Maybe we’d come and watch!

Tunnel built by Philip of Macedon

It was such a great story, and Miller and a few of us who were listening to the story got choked up.

We stopped for lunch at the Isthmus and were able to see the bridge submerge to let the boats go by and come back up to allow foot and automobile traffic. I was madly trying to use the Wi-Fi at the restaurant to make my reservations, but had to abandon the project when I was just about there.

Olivier, Bernard, Lindsey, Dominique, a bit of Leslie, Linda, Sandy, Jeremy, Geneia

Olivier, Bernard, Lindsey, Dominique, a bit of Leslie, Linda, Sandy, Jeremy, Geneia