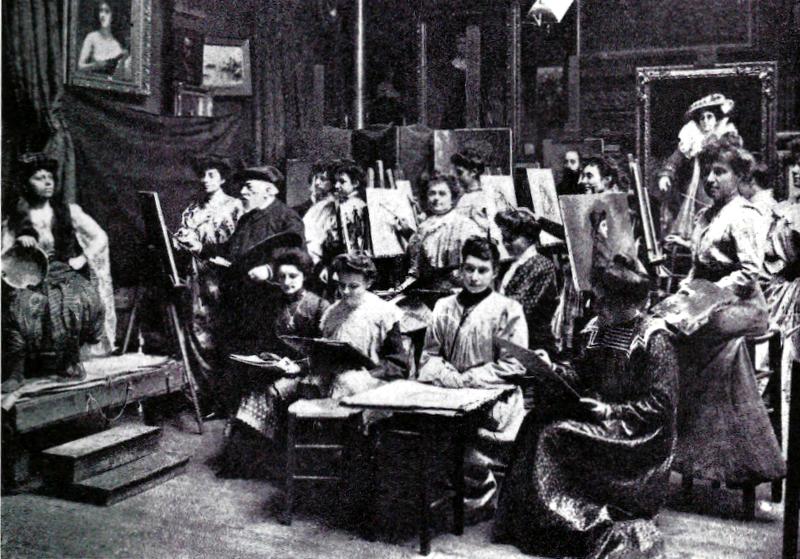

After the Mineral Point Lyceum presentation in April about Orchard Lawn’s Portrait of Ena Hutchinson by Lydia Purdy Hess, I have been conscious that the two women had pursued in their youth an extraordinary adventure, to study in the capital of art, Paris, in the way that only men had studied in the past. They were students at the Atelier Julian, which actively sought female students and put them through the same rigorous training. In May, I attended the Matisse Exhibition at the Minneapolis Institute of Art – another blog – after which I did as much browsing in their permanent collection as I had time to. I’ve visited the MIA a number of times in the past and have my favorites. This time, however, because I had my camera in my hand, I tried to focus on less familiar pieces and artists I didn’t know. Over and over again, whenever I admired a painter’s technique, I would look at his bio and see “studied at the Atelier Julian.” Over and over again! I needed to know more about this extraordinary school.

Myself and Barry Baumann with the Portrait of Ena Hutchinson by Lydia Purdy Hess, before restoration

I should state at the outset that there were others, the Atelier Delacluse, for example, where Purdy Hess also studied. (For female students, the selection was certainly narrower.) Atelier Julian was perhaps the most successful and famous atelier, attracting students from all over the world. I write about it particularly because there is information available. I found and read an exhibition book, Overcoming All Obstacles: The Women of the Academie Julian, and it is from this book that the following information is drawn.

At the time Rodolphe Julian established his atelier in 1868, there was only one state-supported school for women in the arts, the Ecole National de Dessin pour les Jeunes Filles. It was oriented towards industrial design and the applied arts, a mean by which women could earn a blue-collar wage, if not married. There was a prejudice that meant to limit women to domestic or vocational (industrial) instruction, and bar them from pursuit in “fine art,” in spite of the fact that women had been successful in oil painting in the eighteenth century, a time when they were admitted to the Academie Royale.

An expression of its philosophy ran thus: We are not aiming at all in kindling in you an elevated ambition for high art which could lead you away from your true path; we will restrict ourselves to developing in you a taste for beauty, arming you, for a more modest task, with means to realizae yourselves according to your faculties and your needs…The pencil which we put in your hand here must be an instrument of vanity and fame but of modest facility and domestic happiness; it should give independence and dignity to your life and charm and embellish it. You will transmit it to your children like a family heritage.

Julian’s Atelier was initially set up in one well lit room where models were hired for detailed drawing, and well-known artists of the day were hired to instruct and critique the students’ work. Both men and women were accepted and, to begin with, worked side by side. This practice was criticized in some circles and Julian, with the business acumen that characterized him, as well as his no-nonsense approach to education, decided it was in the best interests of the Atelier to create separate studios for men and women to work.

One must strain the imagination to comprehend why a woman drawing a nude model with a man drawing next to her was more risqué than a woman drawing a nude model with a woman drawing beside her. I can only speculate. Models were in it for the money. They were generally working class. There is a well-known convention between male artists and their lower class female models, the world over (accept perhaps in America); these women could have been, potentially at least, the lover of someone or another. And there could have been rumors and rude comments exchanged sotto voce. The male students at Atelier Julian may have been from almost any walk of life. The female students, on the other hand, were almost all from upper middle class families and were used to a standard of gentility in their social interactions. Their families too, who though progressive enough to support their daughters’ serious pursuit of art as a career, certainly would not have wanted to see their daughters’ reputations permanently damaged by consorting with all types, immoral men and loose women. They would have needed assurances of propriety before supporting their darlings’ education financially.

As referenced by Gabriel P. Weisburg, men were trained at considerably less cost than what was charged to women, as it was generally believed that women would be able to find a family member or an outside sponsor who would pay their expenses. The cost of training women artists ranged from 400 to 700 francs, depending on whether she spent a half day or full day in the studio. As much as one might resent this unequal treatment, it is clear that Julian had the commercial success of his venture in mind. He needed money to run it; he wanted to attract talent and he wanted to his students to attain success in the competitive art world.

In spite of the higher prices charged – which might also have been due to having to house his female students, rather than oblige them to find their own digs at added risk – he did encourage them to spend full days in the studio, compete with one another as well as their male colleagues, and develop the mental and emotional toughness that would allow an artist to persevere in the face of adversity and criticism.

It would be interesting to compare the differences in social values that are taken for granted in one’s own set at home, between Paris and the United States. The feminist movement, which gained numerous adherents in France throughout the latter part of the nineteenth century, stressed a woman’s right to select her own path….Women who intended to become professional artists did not want to remain mired in lowly roles where they would be relegated to decorating fans or ceramics. Instead they wanted to be respected in the fine arts community. The feminist movement was not absent in America. There was a serious suffragist movement in the US, at least in intellectual centers like Boston. I speak from ignorance, but it is difficult to imagine that feminism would have been so pervasive in a place like Mineral Point, where Ena Hutchinson haled from. I imagine the intellectual atmosphere of Paris must have had a profound effect on her.

William Bouguereau, The First Mourning

Since most of the women who came to him (Julian) were financially secure and from diverse countries, he hired well-established academicians with extensive international reputations, such as William Bouguereau, Tony Robert-Fleury, Gustave Boulanger, Jean-Paul Laurens, and Jules Lefebvre, to direct his studios and critique students’ works. His hiring such widely recognized artists indicates that Julian well understood how to attract potential clients and students without raising concerns about excessive costs. These instructors, with their own professional contacts, were in advantageous positions to introduce the female students to potential clients and to gain them access to exhibitions and governmental sales, thus ensuring that they were on the right track when their training was finished. Both Bouguereau and Lefebvre, with their lifetime of creative work, enjoyed extensive contacts with artists and collectors throughout Europe and beyond.

Tony Robert-Fleury, The Last Days of Corinth

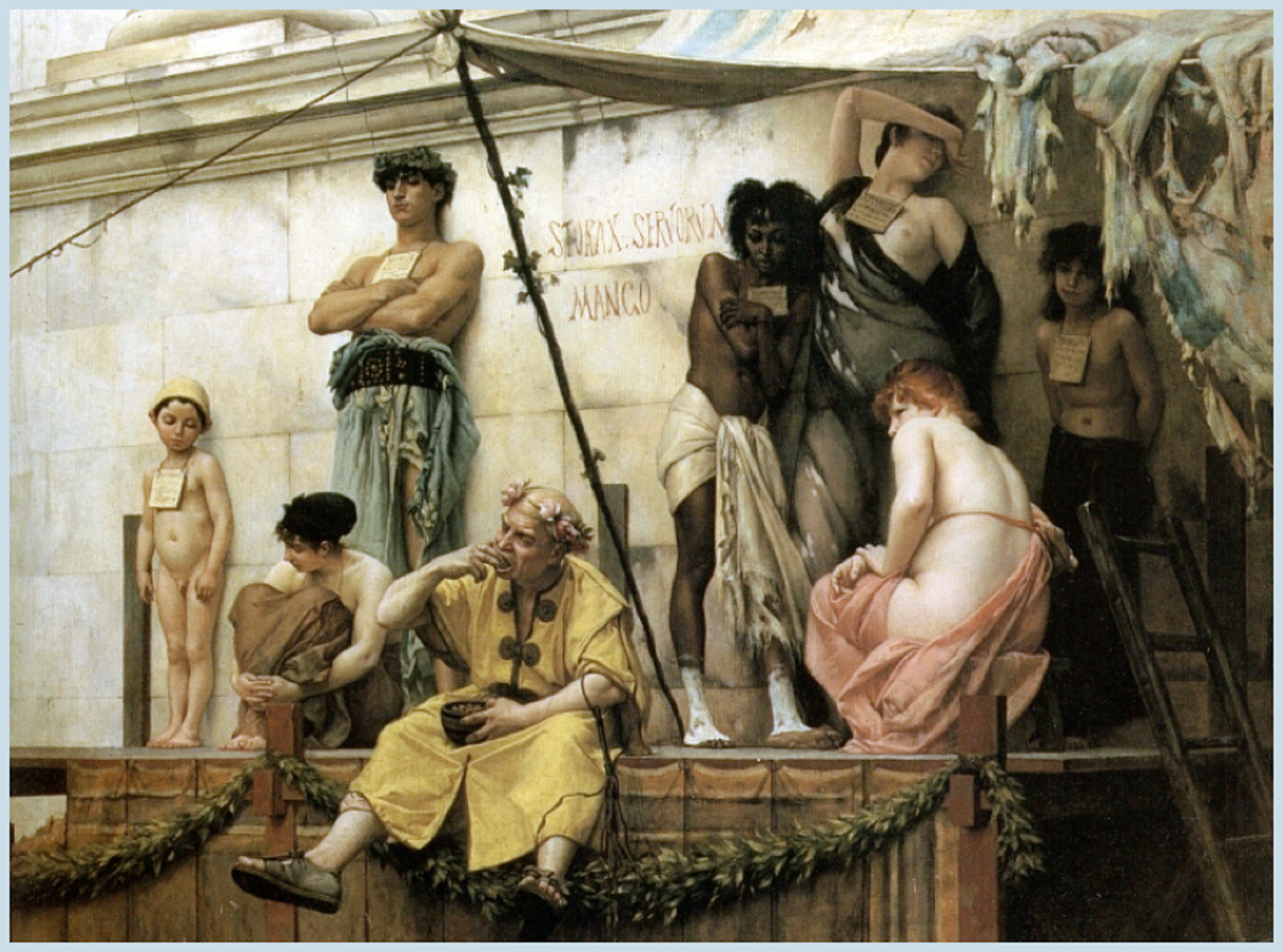

Gustave Boulanger, The Slave Market

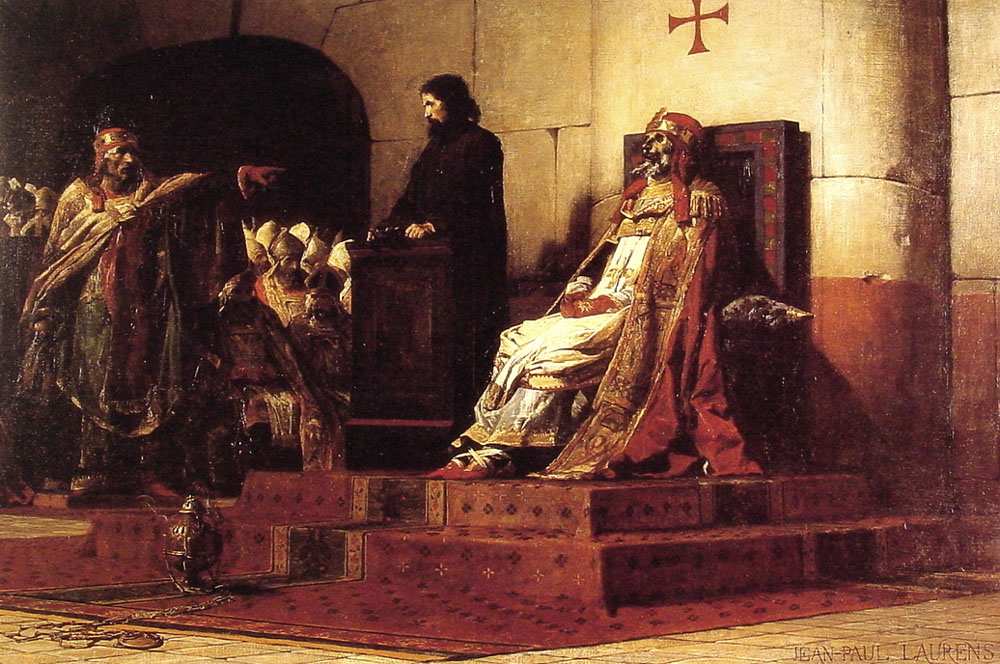

Jean-Paul Laurens, In 1870, when the newly created Kingdom of Italy carried out the Capture of Rome and put an end to the Pope’s temporal power, Laurens made this painting of the Cadaver Synod, a notorious Medieval event in which an excommunicated bishop was tried posthumously for having allegedly tried to usurp the papal throne. Laurens had strong republican and anti-clerical convictions. His paintings are often critical of the Church. It’s interesting that Julian sought out this seeming firebrand as an instructor at his school. He was good-looking too, which makes me think he may have been a particularly interesting, not only controversial instructor, to the international body of female artists.

Through such associations, art instruction for women quickly became both a business and a cause. By 1890 Julian had organized nine different studios, with five for men and four for women. In opening these studios, Julian became an astute observer of the various sections of Paris and of convenient locations that might attract large numbers of potential students and clients. In 1880, one of the women’s ateliers was located near the Palais Royal on the rue Vivienne, not far from the fashionable art galleries in the second arrondissement. By being in such close proximity to contemporary art dealers, students could become aware of changing styles and developing ideas in the art world and also seek the assistance of art dealers in the marketplace.

In anticipation of the Exposition Universelle of 1889, Julian opened another branch of his atelier for female students in an aristocratic section of Paris in the eight arrondissement. He obviously hoped to increase his client base by drawing upon the large international audience that was expected flood the city for the world’s fair. Meanwhile, the Ecole des Beaux-Arts debated whether women were worthy of being trained at all.

Overcoming All Obstacles draws extensively from the writings of Marie Bashkirtseff, an artist born and trained in Ukraine who touted Julian’s openness and effectively campaigned on his behalf. Even though Bashkirtseff was not the most imaginative artist who studied under Julian, her “wit,” elevated social standing in a wealthy, aristocratic Russian family, and tragic early death made her a cult figure among women pursuing their cause of freedom of choice.

She was evidently both flirtatious and a highly competitive personality, especially with Louise Breslau, another student who barely seemed conscious that she figured as Bashkirtseff’s nemesis and chief rival.. ..Her (Bashkirtseff’’s) attitudes must have fueled the ire and amusement of the other female students, which they expressed in their caricatures of her. Drawn when models were resting or when there was a break in class, these caricatures allowed women to work out their frustrations or document their observations in visual form. Others poked fun at their colleagues as a way to alleviate tension and reintroduce an atmosphere of humor.

Jane R. Becker details later in Overcoming All Obstacles the personal conduct of Bashkirtseff and the indignation and humor it constantly occasioned. Bashkirtseff let her “inferior” fellow students know her status by arriving late accompanied by her chambermaid chaperone who supplied her with daily bonbons and her little white wolf dog, Pincio, as well as with her finely corseted dresses, furs, and other fashionable accoutrements. The result was that she was ridiculed in verbal and written form as being out of touch, fat and the teacher’s pet….There is some irony in this last type of representation of Bashkirtseff as she was extremely aware of her self-presentation and

Artist Unknown, Mlle. Marie Bashkirtseff, 1879 (left) and Artist Unknown, Mlle. Marie Bashkirtseff 1878 (right)

wrote endlessly in her diary how beautiful she looked at particular evening events….Breslau Swiss painter Sophie Schaeppi once accompanied Bashkirtseff to her room and were stupefied by the sight of Bashkirseff completely disrobing and lounging in front of them, saying “How do you find me? Aren’t I as well made as those statues that we were just admiring (at the Louvre)?”

This type of memoir, even when spiteful, is the perfect vehicle for taking you there. Who hasn’t known someone like that? Maybe I shouldn’t ask, especially in these days when misguided teenage girls send nude selfies to potential admirers.

However, Bashkirseff’s special place in the studio as the teachers’ pet comes across in visual and written testimonies. Breslau’s caricature may well represent Robert-Fleury holding hands with Bashkirtseff to convey his pandering for her riches and her social contacts. Robert-Fleury appears in period photographs with similar dark features, a short black beard and curlicued moustache, curly hair, and a pointy nose. In another cartoon, Julian himself looks attentively over the shoulder of a well-dressed and well-bonneted

Caricature by Louise Breslau of Marie Bashkirtseff and T. Robert-Fleury

female student, Mlle. Magdeleine del Sarte. His attention to the work of these of fashionable society ladies was remarked upon by some of the other (particularly lower-class and foreign) students. His particular attention to Bashkirtseff is evident from passages in her Journal. By the fall of 1878, Bashkirtseff wrote of Robert-Fleury, “I know that he adores me as a pupil, and so does Julian”; of the students, she observed, “They all envy me.”

She does sound insufferable. However, (in Julian’s defense) it was still unusual for women of Bashkirtseff’s class to come to Julian’s studio at all in 1877, and, for the owner, the young Russian painter was an excellent catch, a means to launching his business on a grand scale. One might compare the situation to that in which Mr. Selfridge finds himself in the first season of the miniseries, wherein his relationship with Ellen Love, the “Spirit of Selfridges,” progresses according to her misunderstanding of his motives. In Marie Bashkirtseff’s defense, actual photographs and paintings of her testify to her comeliness, so Breslau’s cartoon with warts (above) was not visually inspired.

Madeliene Zillhardt, to whom we owe the anecdote about the Disrobing Incident, as well as Mary Breakell, another student at Julian’s from England, both wrote their impressions of how Bashkirtseff’s very entrance into the atelier changed its atmosphere. Zillhardt described the dark and smelly service staircase by which one had to enter the studio in the passage des Panoramas, and she noted that despite this location and such discomforts of the studio as its overheating in the August sun, gaiety and ardor for a place in which to work – a room of one’s own, in Virginia Woolf’s later parlance – reigned. Into this space

entered the “pompous” Bashkirtseff. Before the young aristocarat’s arrival, Zillhardt recalled that none of the students had been rich and that her own sister Jenny played the part of the young patron of the studio because she treated her comrades to galettes and sparkling wine with the pocket money her father sent her. Bashkirtseff’s arrival, followed by her “little negress” and her dog, “caused a sensation.” While the Ukrainian wore a modest working costume of black alpaca, she was “dictatorial to excess,” and “the least obstacle to her will threw her into crazy fits of anger.” After these fits, as slyly as a cat, she would switch into seductive mode, which was crowned by her irresistibly charming smile. Those who were starstruck by her presence and put themselves at her service she rewarded only with leftovers from the meals that her chambermaid, Rosalie, brought her daily. When sitting at lunch with the other students, Bashkirtseff would sit the only available chair. It is not surprising that she felt herself privileged, for, as Zillhardt recounted, Bashkirtseff’s mother idolized her to the extent that she actually kneeled to kiss her daughter’s feet. When not dressed in somber work outfits, Bashkirtseff would appear at an evening’s anatomy lesson already dressed for the theater or ball, with décolleté and stylish long train – hardly the kind of subdued costume one would wear to fit in with the other students at Julian’s.

Breakell noted that the women of the passage des Panoramas, “a Bohemian, ‘barny’ sort of place” prided themselves on their seriousness of purpose, as opposed to the more “dilettante demoiselles” of Julian’s rue Vivienne studio – There was competition between the various Julian Studios, besides the rivalries Julian encouraged between students.

Here is more, by Breakell, on the contrast of their hard, cold mornings, and the professional pride they took in them, with Bashkirtseff’s:

We English girls, among those of many other nationalities in Paris for the purpose of study, worked the hardest, in the deepest earnest. We rose before it was light, and dressed ourselves with freezing fingers. We were out at “first breakfast” in a humble cremerie, drinking our hot chocolate, in thick white bowls like mortars; crunching our crisp rolls with the worthy working folk of Paris in their blue blouses at the marble tables; then trudging bravely, for an hour, through the snowy streets and leafless Elysian Fields and boulevards (for it was bitter cold in Paris that winter of 1882), long before the majority of the Paris students had left their warm nests of homes, long before “the Russian” had stepped into her carriage….(At ten o’clock) French girls, Americans, Italians, Swedes, and English – even an “unspeakable Turk” – we are all chattering in harmonious European concert when the door flies open, and with a flutter and a rustle and a cheerful, ringing, ‘Bon Jour, Mesdames,’ enters “the Russian.” She impatiently unfastens, flings back her costly furs and long silk mantle; right regally she lets them fall to the bare, boarded floor, for the bonne to pick up. Clothes to her are non-existent at the moment (or she would have us think so). She is consciously only of Art.

Snort! Breakell evidently recalled her student days, toughing it out and at one with the serious, working Parisians, with all the warmth that the prima donna Bashkirtseff remembered any tributes from her instructors. In my freshman year at Saint Olaf, an early friend and fellow freshman confided to me that “in her coed dormitory (built as temporary housing, where everyone lived along two crowded halls) men and women were like’ brothers and sisters, intellectual equals,’ whereas girls from Larson (the women’s tower built only two years previously, where I lived), girls were considered only good for” and she described in succinct terms a casual and carnal date. Charming! We didn’t see each other that much subsequently. Presumably she went on enjoying the esteem of her dorm-mates and I continued studying in my Ivory Tower.

Of Bashkirtseff’s search for attention and positive reinforcement from Robert-Fleury, Breakell recalled the way that “the Russian” would look up at her teacher “coaxingly and coquettishly beseeching for praise like the baby she is.” Breakell did allow that this “girl Narissus” was loved, finally, by the inhabitants of the atelier, but as “a charming willful child” is loved.

(This is a true picture of student life. Eventually Bashkirtseff was accepted. She was, in fact, one of “them,” a woman artist who took herself seriously, but more on that below.)

It is not especially nice to recount the folly of a girl’s vanity, but Bashkirtseff is not unlike many young, ambitious, talented and pretty women. Her folly is not unique; it is adolescent. “I truly believe,” she writes in her Journal, “that R.F. has a very correct opinion about me; he takes me to be what I should like to appear, that is to say,…a very young girl, a child even, meaning that while talking like a woman, I am at my heart’s core, and in my own sight, of angelic purity.” Since she was a young girl beginning her diary, Marie had dreamed of being famous; her will to enact this dream is what brought her to Julian’s and to art in general. In Paris in 1877, she traced her newfound devotion to art to God’s own will that she renounce all but her art; she could not bear the thought that her talent might be only mediocre.

I can feel sympathy with her aspirations and even her self-preoccupation – the above was drawn from a private journal after all.. Some of her folly is just too good to pass up though…and besides, she’s dead, so here goes:

When she asked Julian, “pray tell me what M. Robert-Fleury said of me…I know that I know nothing; but he has been able to judge…a little, how I am beginning, and if….” He answered, “If you but knew what he said of you, Mademoiselle, you would blush a little.” In private, he told her that if she were to continue as she had been, she would do wonders and that what she had already done was phenomenal. Marie did not need this confidence boosting; soon enough she believed herself especially gifted in the arts and more so than many of her fellow students. “What I pledge myself to do at the end of the year or two the Danish girl will never do at all.”

She masqueraded as the poor, little artiste in Paris, amusing herself: “I love to go to the booksellers and other people, who thanks to my unassuming dress, take me for a Breslau or some one of that class; they look at you in a certain kindly encouraging way, which is quite different from what I am accustomed to. One morning I went with Rosalie (her chaperone) to the studio in a cab. To pay the man I gave him a twenty-franc piece. ‘Oh, my poor child, I have no change to give you.’ It is such fun!”

On October 7, 1878, Bashkirtseff observed, “Robert Fleury and Julian build great hopes on me; they take care of me as if I were a horse which had a chance of winning the Grand Prix.” She was their winning ticket to success and popularity with young aristocratic female students for years to come. By 1879, Bashkirtseff recognized this fact; she confided to her diary that Julian encouraged her “for the sake of money I bring the studio, and for the honor I might bring.”

Jane R. Becker, who wrote about the Bashkirtseff – Breslau rivalry states that Bashkirtseff generated a cult, much as Frida Kahlo has in our own time. She cautions that Marie’s Journal, despite what I’ve quoted concerning the adoration (or pandering) of her teachers, is actually full of self doubt, expressing apprehensiveness about ther teachers’ opinions. In this last quality, Becker writes, she was very different from Breslau, whose inner strength before the habitual atelier criticisms was unparalleled. Certainly, her personality was more stable than Bashkirtseff’s, her emotions more in check. Bashkirtseff’s self-aggrandizement of her talents and her efforts led her to consider it “absurd that Breslau should draw better than (she did.)” At the same time – in the same diary entry, even – the painter cursed her own lack of skill

in balancing figures, in creating realistic figures and a balanced composition. But comments in her diary and about her skills by later biographers certainly do contrast with Breakell’s and other students’ tales of her sweeping in late to the studio and not working very hard. Her tragic early end in 1884 and the subsequent publication of her diary in 1887 – expurgated though it was – were what led to Bashkirtseff’s immoralization as both an art historical and a literary legend. The fact that Marie’s mother changed the date of Marie’s birth from 1858 to 1860 and all f the corresponding dates in her diary so that she would appear to have been even younger at her death and at the various moments of glory in her life led readers and viewers for decades to believe Marie to be even more precocious than she really was.

Louise Breslau, Bashkirtseff’s nemesis was a hard-working artist whose father had died when she was seven. She had grown up in a single-parent home, learning to be independent and to work for a living. Her father had been a physician and her mother worked at a University. She was not known for her looks and she did not celebrate them herself, either….The caricatures of her…convey that she was focused and serious about her artistic pursuit; she would not easily back away from it. Success, for Breslau, was hard won. Arsene Alexandre described at length her triumph over adversity in his monograph dedicated to the artist of 1928. He explained, “Louis-Catherine Breslau will be…the prototype of those who, following the sacred rule formulated by Beethoven, will have had to pass through suffering to arrive at joy, an admirable joy, but little envied.”…Although private ateliers of famous painters took women, these were usually rich society women. While men had many choices of where to work, foreign young women without money could only be grateful for what chance they were given to work in Paris. Alexandre noted that Breslau never complained about her time at Julian’s and even looked upon it later with great nostalgia.

There is much to tell and see of the skill acquired by the women (not to mention the men) who studied at Atelier Julian. My focus has been not to recount “who’s who” in the pantheon of artists who studied there and there and their subsequent careers, but to glimpse what I could of what it was like to be a foreign, female student studying in Paris, seriously studying art in the time-honored, masculine way Breslau became one of the most successful portrait painters of her day and Bashkirtseff became the poster-child for feminist artists. She died young and her mother published an edited version of her Journal, falsifying her age to add pathos and make her a prodigy. To do her credit, however, her Journal was not all she wrote. She also wrote articles under a pseudonym arguing in favor of women’s right to education and equal professional opportunity.